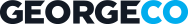

Rising To The Top, MICHIGAN: The Magazine of The Detroit News, June 12, 1988

Date: June 12. 1988 Publication: MICHIGAN: The Magazine of The Detroit News Author: STARK, AL Photographed: TEREK, DONNA

RISING TO THE TOP – Melody Farms’ Mike George used to work a milk route seven days a week. Now he’s point man for a multimillion-dollar family business.

RISING TO THE TOP – Melody Farms’ Mike George used to work a milk route seven days a week. Now he’s point man for a multimillion-dollar family business.

Corporate biographies often start in a tinkerer’s workshop (Henry Ford) or a salesman’s car (Ross Perot). The story of Melody Farms Dairy begins one hot day in 1918 in Telkaif in ancient Chaldea when ll-year-old Naima Shammami, in a gold-threaded dress and a veil, was lifted onto the horse upon which, according to the old custom, she would be carried to her wedding.

The groom was a 20-year-old farmer named Tobia George Lossia. After the wedding he walked through Telkaif leading his bride on her horse door to door. At every house the couple was feted by friends who joined the entourage.

It is said. the Magi stopped to rest near Telkaif, now part of Iraq, on their way home from Bethlehem. Televisions and VCRs are not uncommon there now, but many people still live in earthen houses that have the look and feel of centuries past. When Tobia and Naima were children there was not even a school.

Naima and Tobia’s first child, a son named Sharkey, was born in Telkaif. Andrea, their first daughter, was born there, too.

In 1924, Tobia left Naima and the children behind and made his way to Detroit, where a few others from Telkaif had already located. The first Chaldean known to have emigrated to the United States was a fellow who came to Philadelphia around the turn of the century and did so well that he went home and opened a hotel in Baghdad. Religious discrimination sent some of the young people of Telkaif away; Chaldeans are Christians, and Iraq is predominantly Moslem. Others sought more opportunity than the village offered. Some were just itchy.

Like so many immigrants from so many places, Tobia spoke no English when he got to Detroit, but there was already a small and tightly knit Chaldean community here. Twenty families, perhaps, most from the region of Telkaif. Tobia found work in a grocery store owned by Chaldeans. There he began to learn English, the grocery business and to get used to his new American name, Tom George, the surname Lossia having been lost at immigration and Tobia turned into Tom. When he was ready, others in Detroit’s little Chaldean community made him loans, without interest, so he could buy his own store.

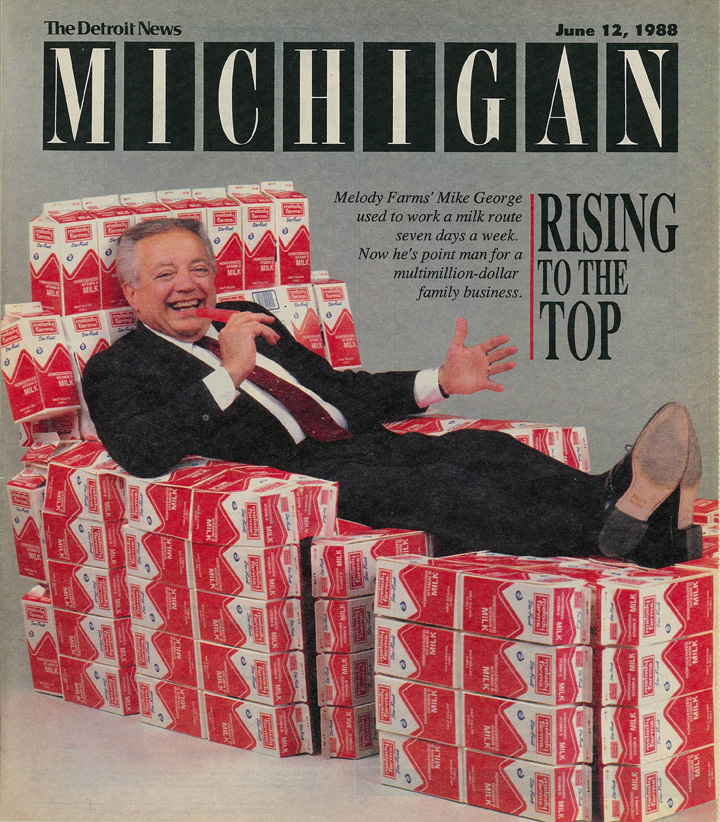

Mike George, Blake George, Rodney George, Robert George, Mikey George, Lenne George, Anthony GeorgeTom George sent for Naima, Sharkey and Andrea in 1929. Another daughter, Margaret, was born in Detroit in 1930. Michael George was born in 1932, on the east side. The last child, Victoria, was born in 1934.

Mike George, Blake George, Rodney George, Robert George, Mikey George, Lenne George, Anthony GeorgeTom George sent for Naima, Sharkey and Andrea in 1929. Another daughter, Margaret, was born in Detroit in 1930. Michael George was born in 1932, on the east side. The last child, Victoria, was born in 1934.

All the children of Naima and Tom worked in the family store, a tiny place at 105 East Palmer.

“I don’t think it was more than 1,000 square feet,” says Mike George. “The whole family worked there. I started when I was 8, sweeping. Then I learned to wait on people at the counter. When I was 12, I started learning to cut meat. By 15, I was a butcher.

“My brother and all my sisters – each one of us is an accomplished butcher.”

Mike George is the one everybody thinks of when they think of Melody Farms, Michigan’s largest family owned dairy, closing in on annual sales of $100 million. Mike is Melody Farms’ chief operating officer and a lot more: As the family has moved into real estate and development, his name is no longer mentioned only in the food industry. Sharkey is an equal partner in the dairy and chairman of the board, but Mike is the visible one.

“Sharkey and I own Melody Farms 50-50,” says Mike. “We’ve been signing over stock to our children every year as the law allows, so maybe it’s 30-30 now. But it’s Sharkey and me.”

A host of independent grocers and party store operators in the metro area, not all but many of them Chaldean, regards Mike as their patron for the start-up money the Georges have lent them. That is both good business – because each operator becomes a loyal Melody Farms customer – and an extension of an old Chaldean belief that one who accepts help owes help to another.

The Georges own real estate of the most prime sort, such as three office buildings on Northwestern. They are building hotels in Livonia and Southfield, have plans for two office buildings in Southfield, and are involved in an office development in the mushrooming corridor along Interstate -275. It was announced recently that they and partners want to build an office tower and apartments on the Detroit riverfront just east of the Renaissance Center.

Then there is the leadership role the Georges, with Mike again the most visible, have taken in Michigan’s growing Chaldean community. That community is now more than 10,000 families and may not yet be properly recognized for its willingness to work as well as earn, for its productivity and its citizenship.

A couple of years ago at Christmas time, Naima George’s grandchildren and their husbands and wives sat her in a chair, turned on a video camera and began asking questions. Tell us about your wedding, grandma. What was Uncle Mike like as a boy? Did he ever get into trouble? Were you really a bootlegger in Prohibition?

The videotape is one of those treasures that should be wrapped in soft cloth and kept in a safe place so these children and their children and the children that come later will always have it. On the tape, everyone talks at once. There is a lot of laughter. Grandma speaks sometimes in English and sometimes in Arabic. She answers the questions she wants and ignores the ones she doesn’t, as is a grandma’s right. An outsider watching the tape can’t miss the affection and closeness between Naima and her family.

It’s no illusion, this closeness. They know her quite well. One year when the family pot was full, Naima and Tom George bought a big old house with white pillars on Cass Lake in Oakland County. They had it remodeled into six apartments, one for them and one for each of their children. Each year, the grandchildren (plus all sorts of cousins) would report to the lake when school ended and spend the summer with grandma. Judging from the laughter on the tape, a lot of happy stories take place there.

“My mother worked in the store when she couldn’t read or write English,” says Margaret George Sarafa, Mike’s sister. “She told the cereals by the pictures on the boxes. She found the right spices by sniffing them.

“During Prohibition, she made liquors such as arrack. She had a chain on the back door and the chain let the door open just enough for the customer’s hand to reach in with the money and hers to hand the bottle out. That money kept the family going sometimes.”

On another tape, Sharkey tells the grandchildren that he spent a few days in the Detroit House of Correction years ago for “funny driving.” One day his mother appeared at the lockup, carrying something long rolled in newspaper. A suspicious guard demanded to see it. It was a cucumber for Sharkey, who loves them.

Tom George, who died in 1958, was a man of some standing in Detroit’s early Chaldean community, his children say, and he often looked in on newcomers to see what help they might need. He took Mike along on one of these visits, and that is how Mike met his wife, Najat, who was 15 and just arrived from Iraq.

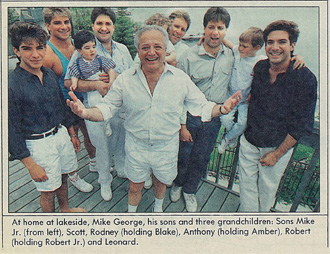

Mike George, Steve George, Robert George, Melody FarmsOn the grandchildren’s tape, Naima George is asked about Mike. She laughs and waves a hand at the camera and says something about screwdrivers.

Mike George, Steve George, Robert George, Melody FarmsOn the grandchildren’s tape, Naima George is asked about Mike. She laughs and waves a hand at the camera and says something about screwdrivers.

“Mike was always into something as a child,” Margaret explains. “She mentioned the screwdriver because he would unscrew all the doorknobs and then get the screws mixed up or lost so he couldn’t put the doors together again. He was always doing something.

“Today he’s a workaholic.”

“That’s the truth,” says Joe Sarafa, Margaret’s son and Mike’s nephew, a lawyer and executive director of the Associated Food Dealers of Michigan. “I have a meeting with Mike every two weeks, in the barber shop. He takes the 9:30 appointment and I take the 10:00 appointment. I get there at 9:30 and we talk while he gets his hair cut, then I get in the chair and we talk another half hour. That’s our meeting, that hour in the barber shop.”

When Tobia George came to Detroit in 1924, the Chaldean community was small and dose-knit. It is estimated that prior to 1939, there were perhaps 80 families, numbering 600 to 700 persons. They all knew each other, sometimes from Telkaif. They did business together; almost all were in food. They made marriages for their children, and their families were joined in the blood of the grandchildren. Most would go to the same weddings and funerals. Most belonged to the same Catholic parish.

A newcomer, often a relative or an acquaintance, would be taken in by this community, put to work, and helped in his adjustment to quite a different sort of place. Eventually, when he had shown he was willing to work hard and long, he would be loaned money to start his own store. That’s how the Chaldean presence in the food business grew. Mike George says it wasn’t unusual in those days for someone to be given 20 loans from 20 families, without interest, pay it back when you can, with nothing written down.

“When that person was established and on his feet, he helped the next one.”

The Chaldean community has grown astoundingly. The present 10,000 families in southeastern Michigan include an estimated 50,000 persons. No longer is it possible for one Chaldean to know all the others. When Sharkey and Mike George sit down with Melody Farms’ bankers today, the bankers are no longer senior Chaldeans gathered around someone’s kitchen table, but downtown bankers who might not be able to find Telkaif on a map. No longer are Chaldeans found only in small stores in the older neighborhoods of Detroit, but they have spread throughout the region, in bigger and bigger ventures. There seems to be no limit to their enterprise.

Yet, for all the growth, for all the movement into the mainstream, neither the family closeness or the ethnic closeness has been cut away.

Mike George has his office on the third floor of a building he and partners own on Northwestern near 13 Mile Road. Sharkey, who owned the Sharkey’s Markets that were in business for years on Beaubien, John R and Third Street, is in the adjoining office. Their sister Andrea is the receptionist in the lobby. On the wall behind Mike’s desk hang pictures of his and Najat’s six sons – Anthony, Bobby, Rodney, Leonard, Scotty and Mike.

Anthony, Rodney and Scotty work for Melody Farms. Lenny works for Compri Hotels, in which his father is an investor. Bobby has his own food business, Western Snacks, mainly meat snacks of which beef jerky is one. Mike, the youngest, is in high school.

Partners in the office buildings along Northwestern include more family the Jonnas, Ed, Jim and Manuel, first cousins of the Georges. Ed Jonna is well known for his Merchant of Vino stores. Salim Sarafa, Margaret’s husband, Is in stores and real estate. Buddy Atchoo, also in stores, married Victoria George, youngest child of Tom and Naima. Mike George helped Jim Jonna start his construction business; now they are partners in development.

It is the generation after Sharkey, Mike, Andrea, Margaret and Victoria, in every ethnic group, in which close-knit families begin to splinter. Instead of growing up in the same neighborhood, where family is a constant presence, this generation moves across the country and even across the world. Eventually, cousins have to be introduced to each other. But Naima George’s grandchildren seem bent on not letting this happen to them. Once a year, they rent a bus and go off on a trip together. The Kentucky Derby this year. A Detroit Lions game out of town another year. Montreal another year.

“We do it so we don’t lose the closeness,” says Joe Sarafa.

Mike George’s sons, and the wives of two of them, are at Mike George’s spacious lakefront home in Oakland County every Sunday. That’s family day for the head of Melody Farms. A wonderful lunch of Chaldean food is spread out on the big butcher block in Najat George’s kitchen, and family and friends are invited to try everything. Salim Sarafa says, with seriousness, “All Chaldeans have high cholesterol.”

On the lower level of Mike’s house, in a little room off the swimming pool, is a large freezer reserved only for ice cream, many of the flavors Melody Farms markets and some others, too.

“Want to know my favorite?” asks Mike. “The popsicle. Ever since I first tasted one as a kid.”

Melody Farms began because Mike George had outgrown screwdrivers and doorknobs and was itchy. It was the 1950s. The family then operated a small supermarket at Pallister and Poe, near Ford Hospital in Detroit’s New Center area. Sharkey had turned the store over to Margaret when she became 18 and had gone off to start his own stores. Mike cut meat there.

Mike says, “I didn’t like looking at four walls all the time, like you do in a store. I preferred to be outside …

”My father had had a little dairy business before World War II, a few commercial customers, but he had given it up when the war started because he couldn’t get the kind of help he wanted. I thought I’d like to start that again, so what I would do is go to the store and when I had the meat cut for the day I’d go out and try to solicit dairy customers.”

Mike George is 55 now, a short, chunky fellow with no airs and an abundance of energy. His idea back then, in the early days of the dairy business, was to hook up with one of the big dairies as a distributor. Sharkey had already become an ice cream distributor for a big company. What Mike wanted his father to do was drop the smaller dairy Tom George had always done business with and sign up with him. Tom George balked. The small dairy had served him well, and he was loyal to them. He refused to change dairies for his son, but Mike said he would go ahead anyway.

Margaret says, “At first, Mike couldn’t get his milk moved anywhere, and rather than take it back he’d bring it to us at the store at Pallister and Poe. We had so much milk from him that we didn’t know what to do with it, and we had to call Family Dairy and tell them to skip us. That went on and Mike’s milk kept piling up, and finally my father and Mike went to Family Dairy and said we were going to have to change.

“That’s when Mike really got started in the dairy business. The first company was called Tom George and Sons.”

Mike says, “For a long time, the only business I could get was from my relatives who had stores. What I learned out on the street was that the big dairies made it a practice to lend money to the merchants who took their products. That tied the merchant to the dairy that helped him, and I couldn’t compete with that.

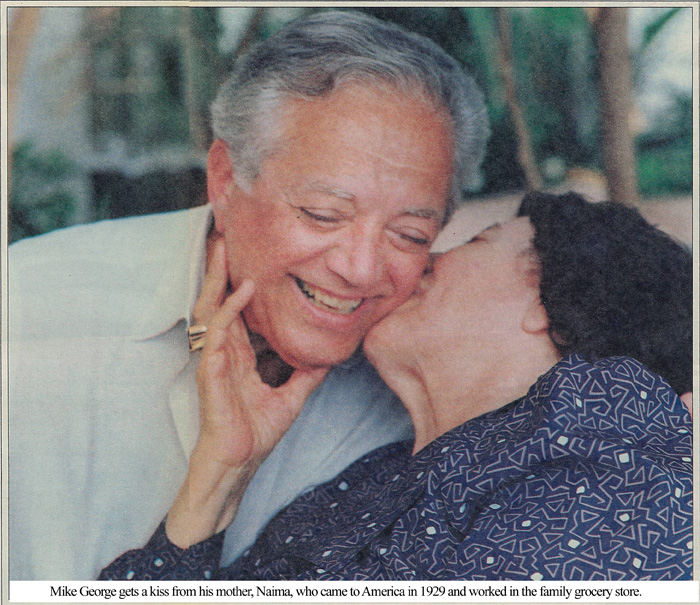

“I went to my father and mother and we talked it all over, and he mortgaged his house for $6,500 to help me get going. That meant I could at least offer merchants what they were getting from the other dairy companies.Mike George with his mother

“I went to my father and mother and we talked it all over, and he mortgaged his house for $6,500 to help me get going. That meant I could at least offer merchants what they were getting from the other dairy companies.Mike George with his mother

”Until 1962, I worked on the milk route seven days a week.”

The first big dairy with which Mike George signed was Wilson. Sharkey had been with Fairmount, and the brothers handled both. In 1962, they bought out a Twin Pines Dairy distributor and started calling themselves Melody Farms. By 1975, they had done business with Wilson, Fairmount, Twin Pines and Sealtest; they absorbed some of those and watched others go out of business as the old-line dairy business went through a big shakeout.

In 1977, they reached a deal with Michigan Dairy to make a line of products for the Melody Farms label. They were getting big themselves, and bigger all the time. Now they have built an ice cream business with more than 50 flavors, and are bringing out their own fruit juices.

“I’ll tell you how the name Melody Farms came about,” says Mike. “We were distributors for Wilson when they first brought out homogenized milk. They advertised their homogenized as Mello-D. The cream, which used to sit on top of the milk, was all mixed in now and this was supposed to say the mix was mellow. Mello-D.

“Customers would call us and say they wanted five cases of Mello-D quarts and five cases of Mello-D. Mello-D. Mello-D. My brother Sharkey said to me, when we were coming out with our own line, that maybe we ought to use the word Melody because people were used to saying it. That’s how we got Melody Farms.

“Later I was told that of all the words in the English language, the word ‘melody’ is one of the top 10 of those that people like to say, just because it is so pretty. But we didn’t know that when we picked it.”

As the business grew, the George brothers continued to help merchants who would be loyal customers, lending money for new businesses and to expand existing ones. Party stores, neighborhood groceries, superettes, big independent supermarkets began coming for help. Mike says that for years, this was done in the old Chaldean way: agree to a deal, shake hands, no paper.

“Some years ago, when our dairy business was still young, we went to Detroit Bank & Trust for a loan. We told them we had X dollars out on loan to our customers, and they said ‘Let us see the notes.’ We. told them we didn’t have notes. They said, ‘You gotta have notes.’ We never did get that loan. I think they finally decided we weren’t their kind of businessmen because their kind have notes.”

Eventually, as things got bigger for the Georges and Melody Farms, the brothers formed a subsidiary called Metro Detroit Investment Co. to funnel money to storekeepers.

Michael George says Metro Detroit Investment now has roughly 200 loans and investments, for a total of about $12 million. It also processes about $25 million a year in loans from other sources, such as the federal government’s Small Business Administration. All 200 current loans are to minorities, he says, 60 percent of them Chaldeans, 10 percent blacks, the rest people from a lot of different groups.

“Every one of them is someone who can’t just go to the bank by themselves and get money,” says George. Who gets these loans?

“They have to be recommended,” George says. “That is very important. They have to have experience in the food business. They have to bring something. In other words, they have to show us what they can borrow first from their families and friends. We look at the store they want to buy or the neighborhood they want to open in. Can it support another store? Will the cash flow be right, so they can pay their bills and make a living, too? Then we check their background and their references.

“We don’t know everyone in the Chaldean community any more. It’s just too big. But it is still true that we are going to know somebody who knows the people who come to us. Most of the time, we know pretty much who people ate, what they do, how they act.

“If something goes wrong in a store we’ve loaned to, we go in. Maybe we reamortize the operation or restructure it in some way. Maybe we send someone in to talk to the owner about marketing, if that’s what’s needed. We can send someone in to take over the operation, to run it until the owner gets the idea. We’ve sold stores.

“There are a lot of ways we can help.”

Some while ago, Melody Farms’ growth was brought home to Mike George in a way that really registered on him, because it was a vivid measure of the long way he and his family have come since he, his brother and his sisters were children. That was when the accountants and consultants told him the business had grown so much and in so many directions, the dollars were getting so big, he was at the center of so many things, that it would be a dereliction of duty if he didn’t let the business insure his life heavily.

Accountants think of things like that. Mike George says he thought of the store on Palmer, where he first went to work sweeping floors.

“There were no salaries when we worked there as kids,” he says. ”Everything went into the family pot. When you needed something, it came from the pot. Years later, when my father was ill and Sharkey and I were running things, it was the same. Every night we’d come to our father and give the money to him, as a courtesy, as a respect. That’s how we were used to doing things. There was a family pot.

”I had to stop and think when this insurance thing was brought up.

“You know, from the 1950s, when we went into the milk business, until we were in the 1970s, my brother Sharkey and I still operated in the old way. All those years, we shared the same checkbook.”